‘sup?

Today, I hope to cover all that I’ve learned and reflect a bit. My contributions to Software Heritage started with very minor bug fixes. After warming up with this, I went on to write indexers for Packagist (metadata file: composer.json) and dart (metadata file: pubspec.yaml) packages. On the way, I found out about the true potential of VSCode and the tools it has to offer (the debugger is on steroids people). Sourcegraph is another project I found extremely cool and think I’ll be using it quite a lot in building and writing edge test cases for the indexers I’m making.

<!–

–>

Codemeta, Schema, & SPDX are central to the indexers of Software Heritage and so I’ll write a bit about them. In the last blog, I briefly touched upon how web 3.0 is the web of knowledge connections, the semantic web. Projects like Wikidata are an embodiment of the semantic web and act as central storage for structured data. Working on this extracted metadata is Software Heritage’s own semantic search module, swh-search, and so there’s a section in this blog for that.

vscode

Until recently, I’ve used VSCode as a code editor, you know? Just like Sublime Text, Vim, or notepad for that matter. Hold on! VSCode just felt too cluttered and intensive on my CPU for writing programs for my Intro to Programming course and programming assignments. And thus, I’d run Sublime (which a friend brought to me) or Vim along with a terminal window. Until I stopped being a dummy *wink. Well, I switched to VSCode around February of this year just because I got access to GitHub co-pilot (I can sense another blog’s worth of content to discuss this technological marvel). And yet, I wasn’t the VSC power user you’d naturally expect one to be. Here are the two things VSC that I’m using for a far more efficient workflow.

- The Remote Development

- The Debugger

Remote Development Using SSH

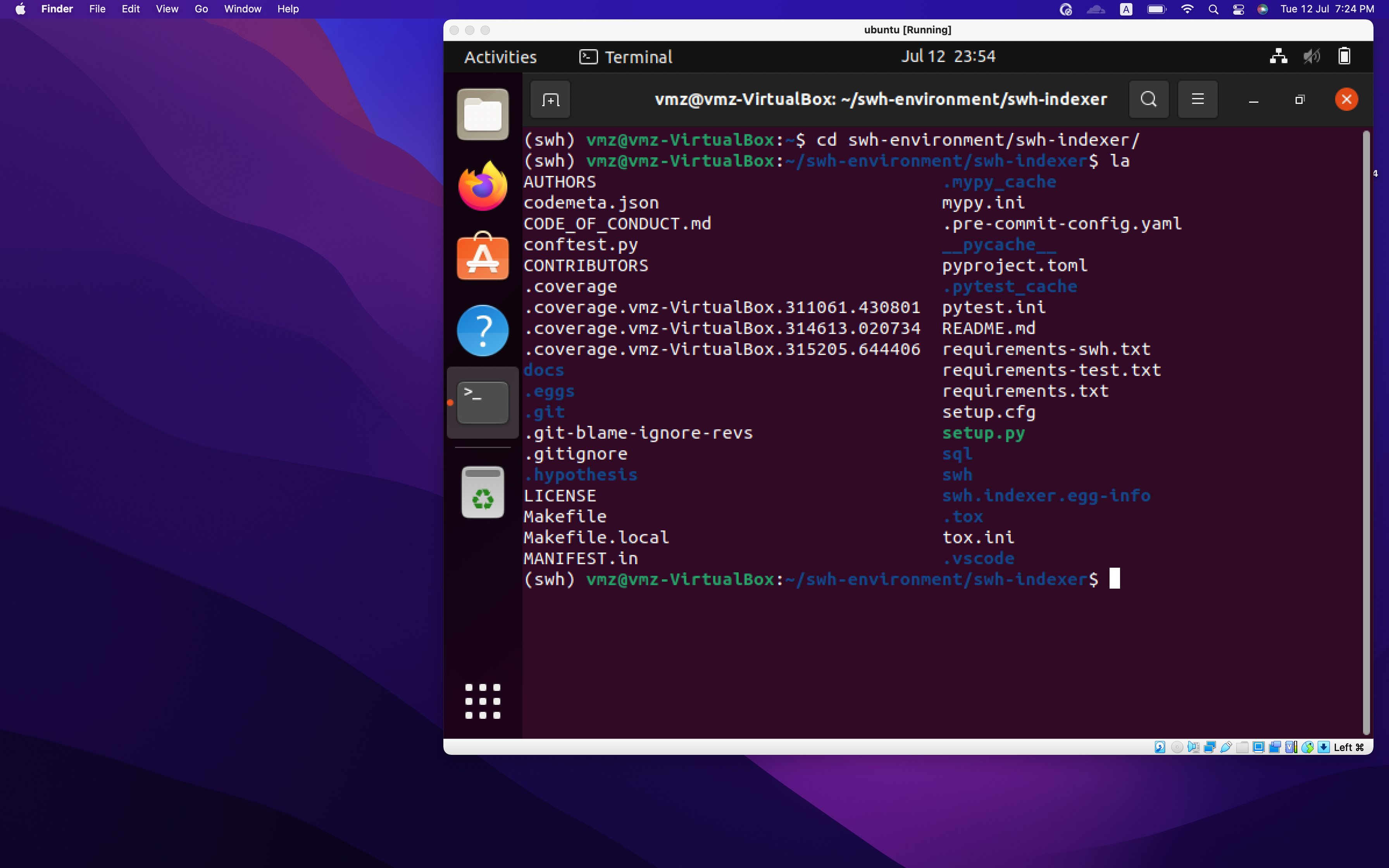

Around March, right around after my first open-source internship (FOSS OverFlow), I started searching, a bit seriously, for Open Source organizations that I could contribute to. I realized that most projects’ dev environment was Linux-specific. And why not, right? Linux is to developers what the Vatican is to Catholics for the lack of a better analogy. Problem is that I had a mac. So, I did what most others may have done. I set up my VM and worked from it.

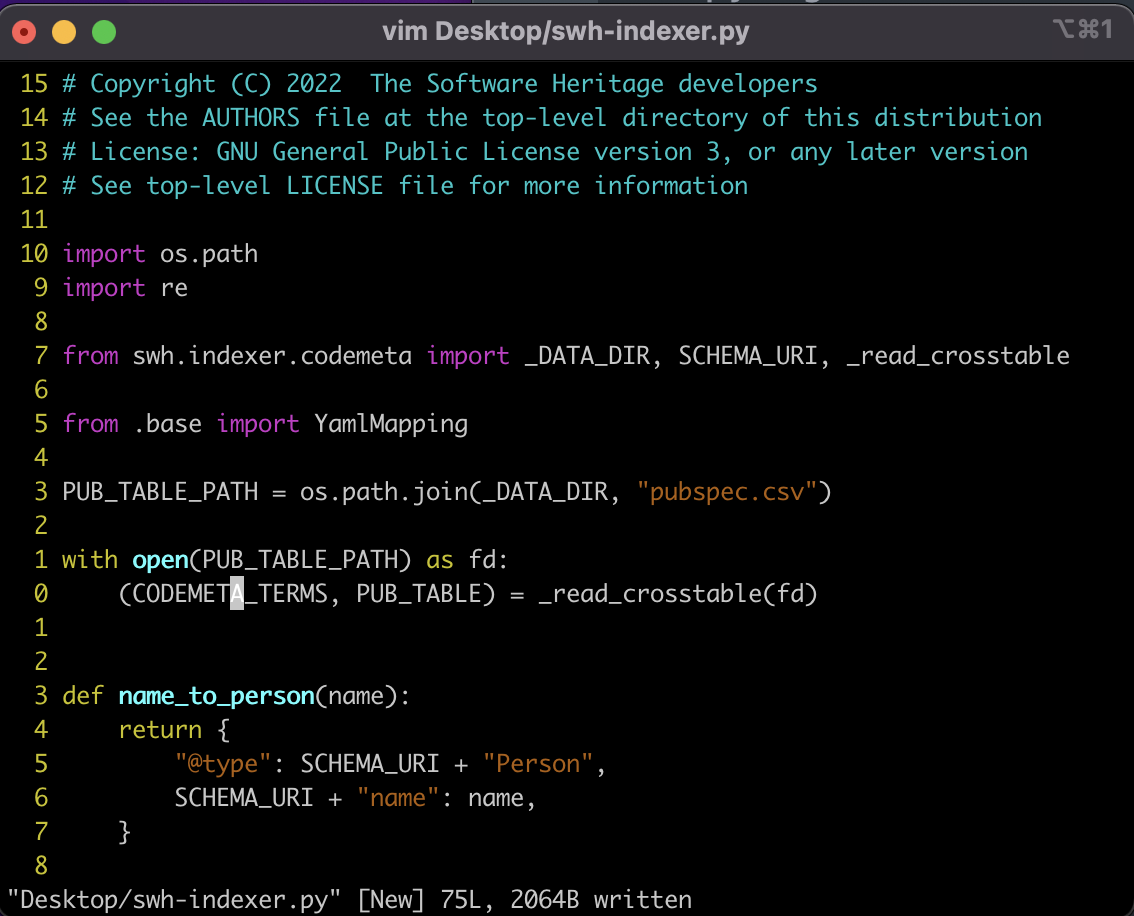

Before

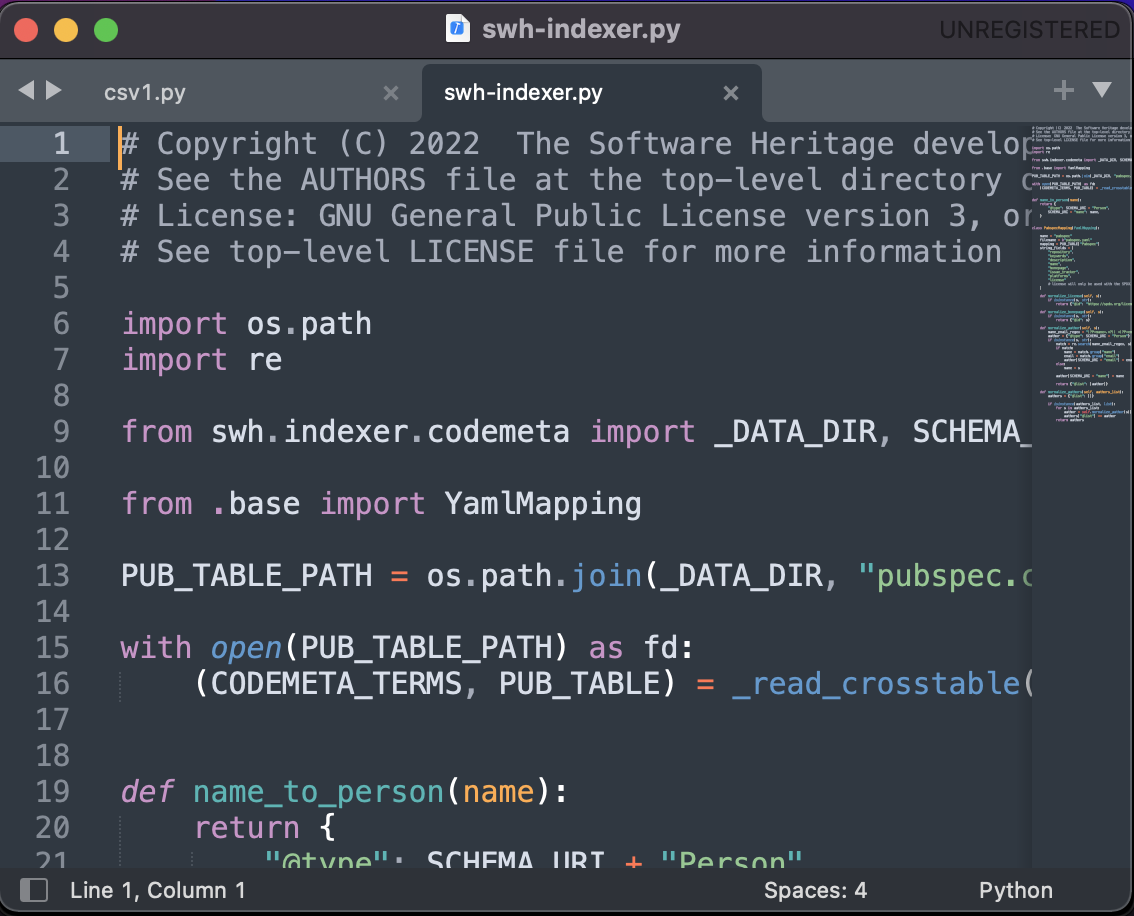

And god was it a pain, for the graphics were so bad in spite of giving it ample resources (4GB graphics and 8 of my 16GB of RAM). Yet, I bore with all the glitchy, laggy virtual machines as it was the only option I had. Or so I thought. A couple of weeks ago, my mentor, @progval, suggested that I use VSC to connect to my VM remotely via SSH and develop on it. I did and I am glad I did for I can’t imagine how much time it has saved. I no longer have to deal with the crappy graphics of the laggy VM. I just get the VM up and running and VSC has automated the process of connecting to it.

After

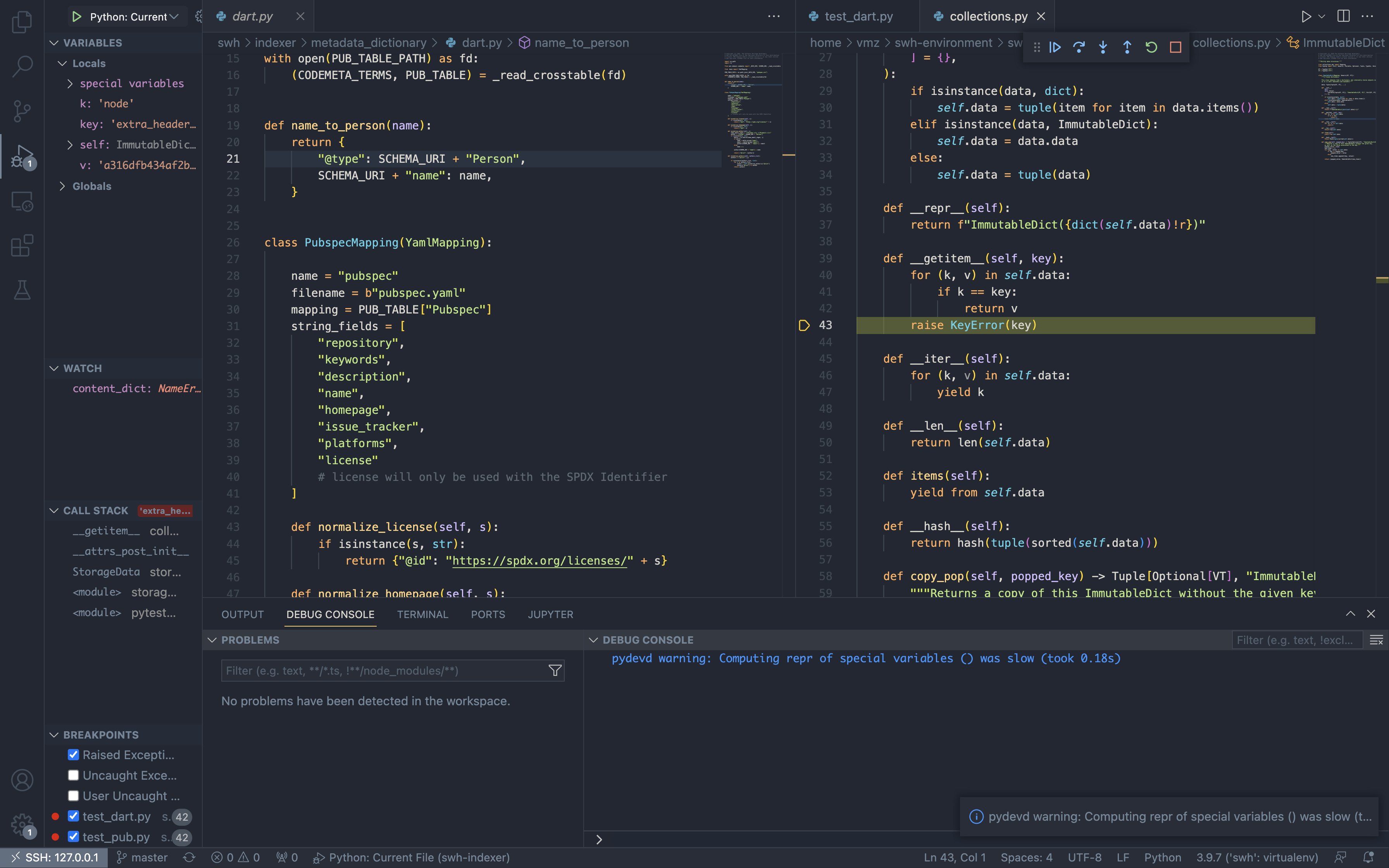

Debugging Using VSCode

I should probably shift the position of this section to maintain chronology. Not that it changes anything though. Before I understood the debugger, I’d use GitHub, of all things possible, to debug my code. In my defense, I wasn’t using VSC yet since I hadn’t set it up for remote development on my VM. Anyways, here’s how I worked. If I found a function, GitHub would allow me to see the definition if I clicked on it. I’m ashamed to put this out there, but it is what I did. This is worse than using VSC’s go-to definition.

Anyways, now I’ve got my own debugging setup with config files (nothing too fancy, I promise). I use the Python extension for VSC to debug. Far from being a pro, I’m comfortable with using breakpoints to dive through code confidently with the debugger as my inflatable in case I drown. Pardon me for the analogies, but I can’t resist since it’s been a while since I’ve blogged.

- The Debugger is the main window that you’ll see when you start debugging. It has a lot of tabs, each tab is a different part of the code you’re debugging. The first tab is the source code, the second tab is the call stack, the third tab is the variables, the fourth tab is the breakpoints, and the fifth tab is the watch.

- The call stack is a stack of functions, the current function is the top of the stack, the previous function is the second top, and so on. The variables in the call stack are the local variables of the function.

- Watch helps you to see the values of any particular variable you’d like to, well *shrug, watch.

- Breakpoints are the actual lines of code that you’d like to break on. Step into, step over, and step out are the other debugger commands you can get the hang of as you work with ‘em.

My debugging setup

And a ton of other things. Just get to the docs by clicking on the title of this section.

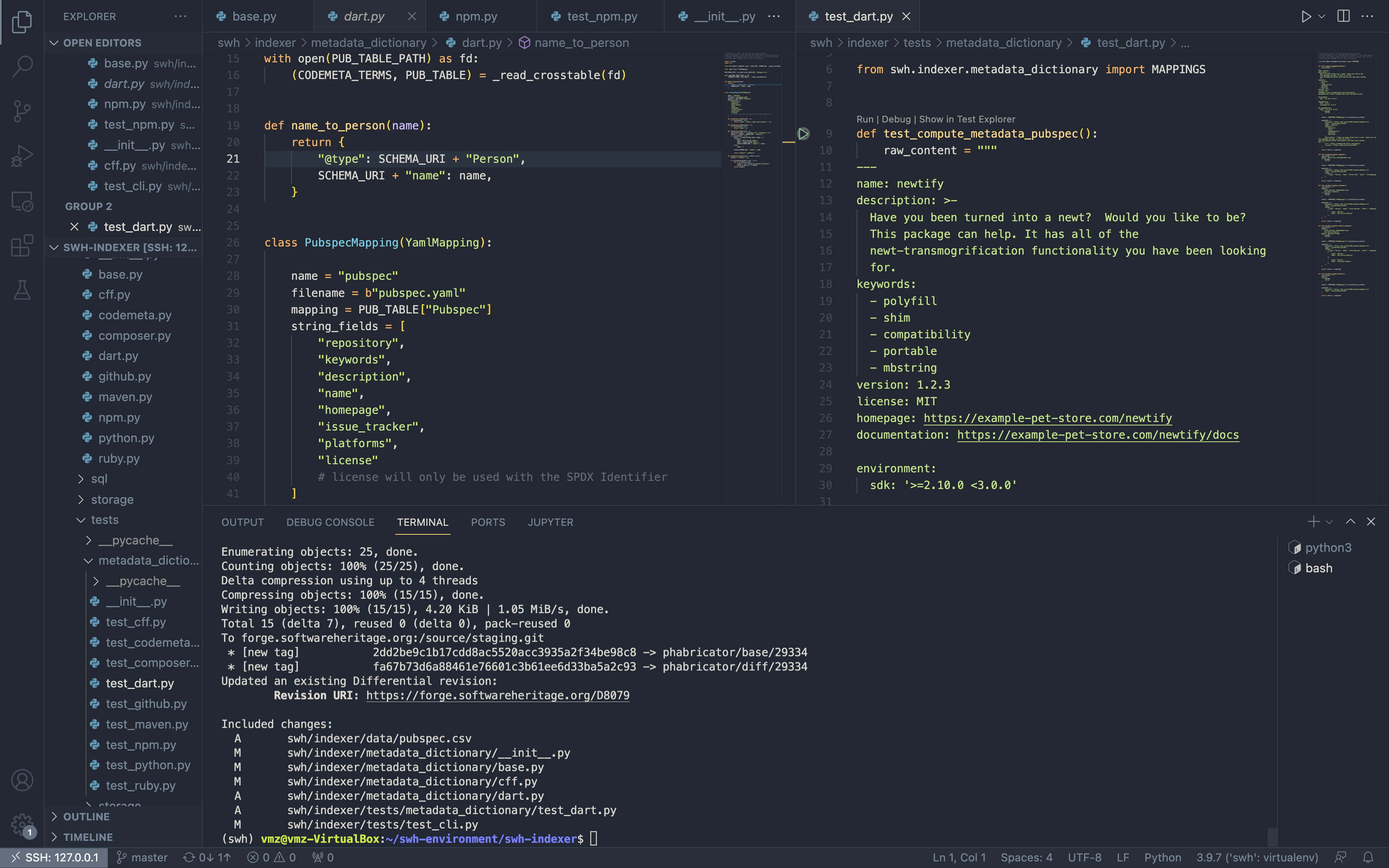

ComposerMapping and PubspecMapping

At first, I thought there’ll be 2 sections for this… But no. Not much to write about the indexers I’ve added to swh-indexer. Combined, I might have extended the indexers to cover more than 400k packages. Here’s what exactly happens with current SWH indexers. For each mapping, there is a column in Codemeta’s crosswalk table. Each field is checked to be in the column and mapped to the property column. Each entry in the property column has a Schema URI. More on this later.

Anyways, for the ComposerMapping class, it was pretty similar to the NpmMapping that was already present. Both work on JSON files. So it was inherited from the JSONMapping class. Initially, I added a column to crosswalk.csv for the ComposerMapping to use. The column was called Composer. My mentor pointed out that this would make Codemeta’s citation inaccurate. So instead, I’ll be putting the new mappings each in a separate file like composer.csv or pubspec.csv. These CSVs have only 2 columns; one for the property name and the other for the respective mapping (i.e. composer or pubspec).

Another interesting thing that was happening while I was building the mappings was the reorganization of tests of the mappings. Earlier all tests for the mappings were in the test_metadata.py file. Now, they’ve been moved to individual files like test_«MAPPING_NAME». A lot better organized now. Three cheers for my mentor who landed those. These changes landed after I had branched from origin/master to build ComposerMapping and I was afraid I’d make a huge mess of git but I’m glad to say I didn’t. VSC is a savior in dealing with rebases or merges.

Here comes the completion stamp:

BOOM

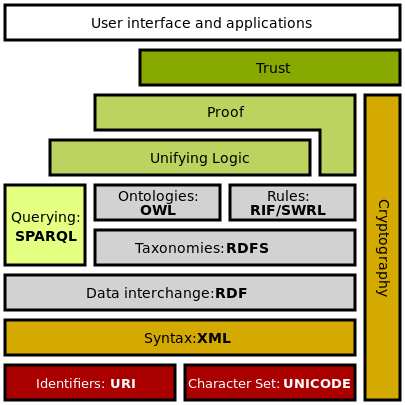

The Semantic Web

What is schema trying to do? What is Codemeta trying to do? Why are they doing what they do? What are RDF and OWL? Where do they fit into the picture? So here’s the thing.

The internet is full of data. This data can be used to make machines do a lot more things than they already are. The goals of the semantic web are to make this internet data accessible to machines. In other words, make this data machine-readable. Here is where technologies like Resource Description Framework (RDF) and Object-Oriented Web Language (OWL) come into play. They enable the encoding of semantics into data.

The term Semantic Web was coined by none other than Tim Berners-Lee for a web of data that can be processed by machines. These standards promote common data formats and exchange protocols on the Web, fundamentally the RDF. According to the W3C, “The Semantic Web provides a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries.”[5] The Semantic Web is therefore regarded as an integrator across different content and information applications and systems.

Here’s a quote expressing Tim Berners-Lee’s original vision for the Semantic Web:

I have a dream for the Web [in which computers] become capable of analyzing all the data on the Web – the content, links,

and transactions between people and computers. A "Semantic Web", which makes this possible, has yet to emerge, but when it

does, the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy, and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines.

The "intelligent agents" people have touted for ages will finally materialize.

I’ll pick the semantic web stack illustration from somewhere (can’t remember exactly where I found it first).

The Semantic Web Stack

But to understand what it’s all about, you can check out the Wikipedia page. That’s where I learned about the Semantic Web. :-)

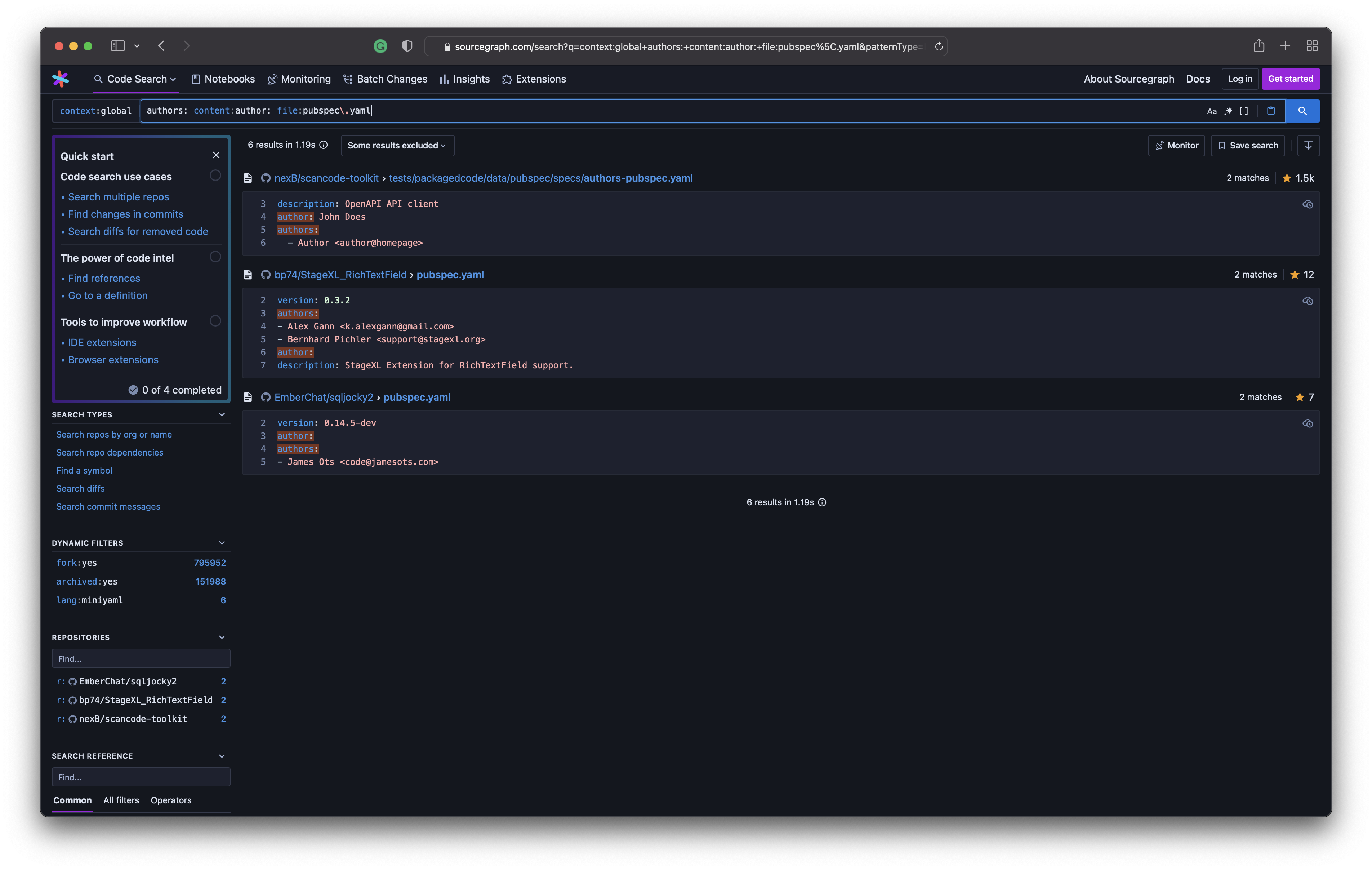

Sourcegraph

At this point, I’m wishing I’d blogged more frequently so I wouldn’t have so many things to put in this blog. Anyways, Sourcegraph.

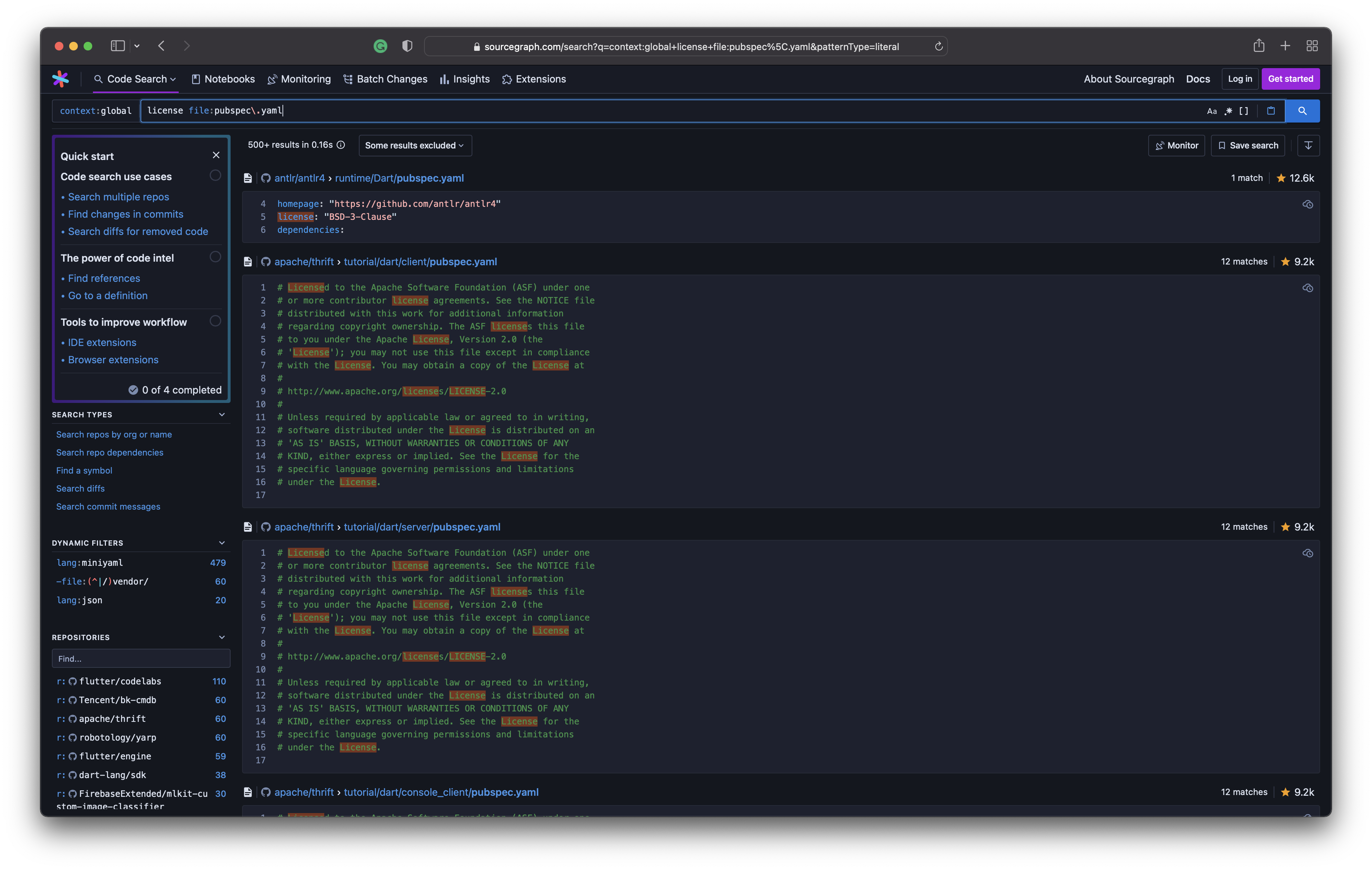

At its core, it’s a search and navigation engine for software source code. It’s offerings can be distinguished into Sourcegraph Cloud, Sourcegraph Enterprise (for your own environment) and Sourcegraph OSS (for limited functionality like code search, browsing and navigation). You can use search strings, regexes, symbols, and references or like I did, file names and field names in the file.

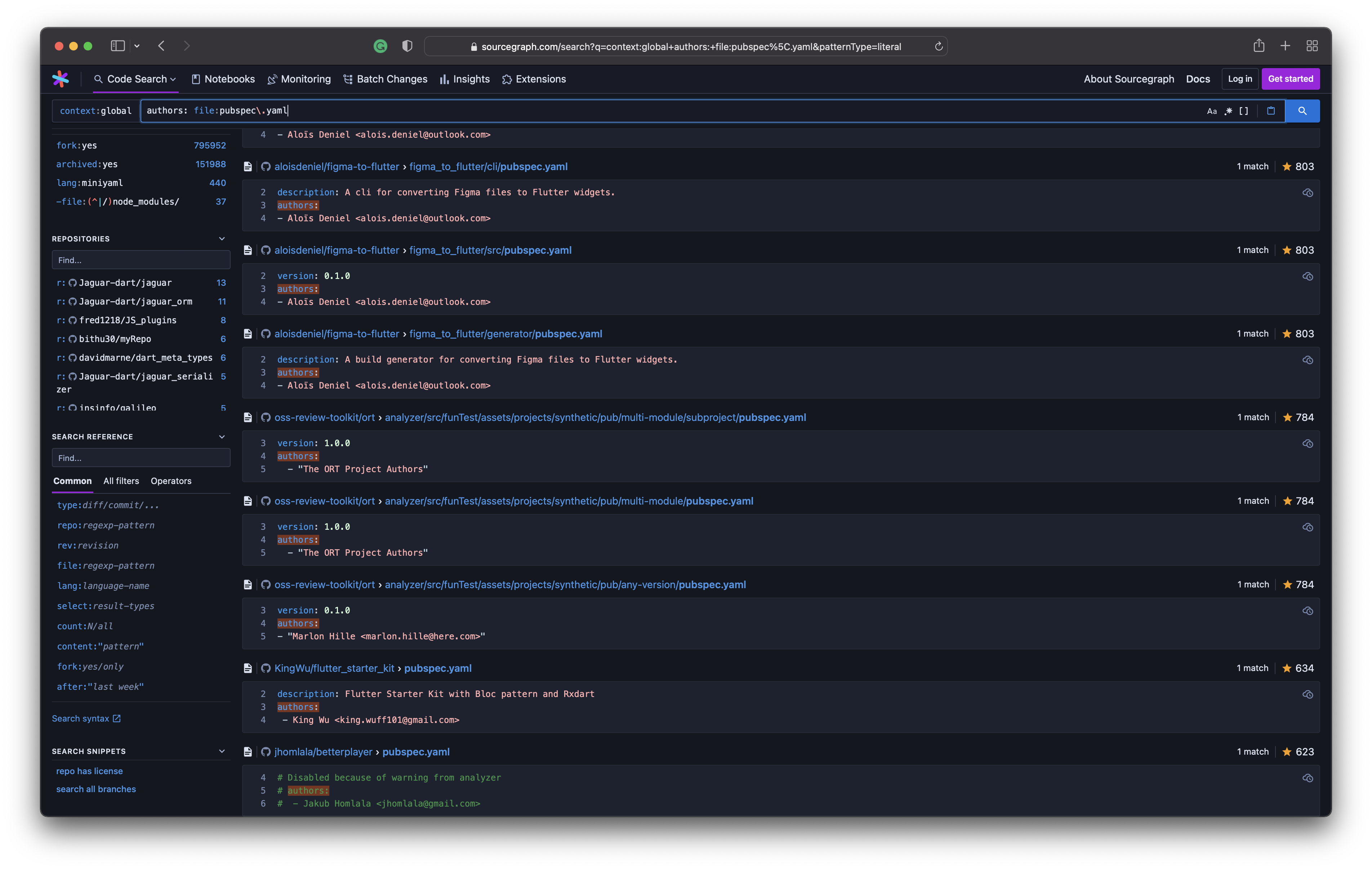

I needed to check if the license field that was in pubspec.yaml files were indeed set to a value supported by SPDX. In another instance, I had to check whether author(s) values contained email IDs in all cases as it is optional. Turns out that an author can only contain a name without an email ID. So I kept that in mind while coding the normalize_author method into PubspecMapping.

A lot more than this can be done with Sourcegraph. I’m looking forward to using it on my poor juniors should they choose to submit plagiarised code for OpenLake Hackathon submissions.

Oh, and yes! Here’s another search string I used to query sourcegraph. I needed to check if both author and authors fields are present in pubspec.yaml files.

Here are the queries I made:

- Query 1: license file:pubspec\.yaml

- Query 2: authors: file:pubspec\.yaml

- Query 3: authors: content:author: file:pubspec\.yaml

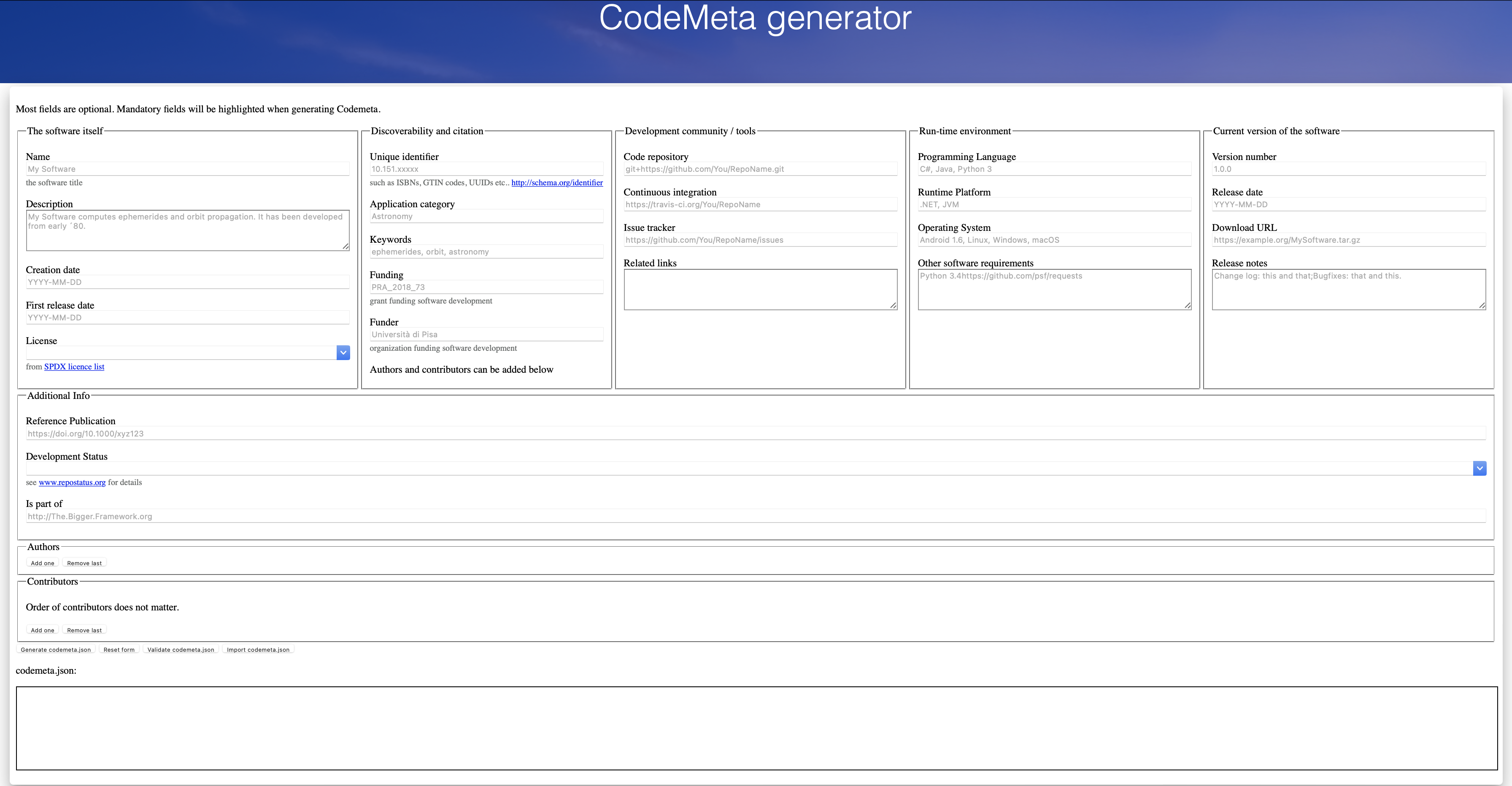

Codemeta, Schema, & SPDX

It all started with the study in Hannay et al. 2009. A growing fraction of researchers is engaged in developing software as part of their own research. Metadata required depends on the sort of project undertaken. To credit academic software, citation metadata is important. In replicating analyses, version and dependency metadata is important. Codemeta offers a simplistic and minimalist schema for scientific software and code. At its essence, Codemeta is an attempt to standardize the exchange of software metadata across repositories and organizations. It is a darn good attempt too, thanks to the crosswalk table that it offers.

Codemeta generator

If Codemeta offers the table to map fields of different packages into a standard format, Schema defines what each entry in the crosswalk table should represent. Schema.org vocabulary can be used with many different encodings, including RDFa, Microdata, and JSON-LD. These vocabularies cover entities, relationships between entities, and actions, and can easily be extended through a well-documented extension model. Over 10 million sites use Schema.org to mark up their web pages and email messages. Many applications from Google, Microsoft, Pinterest, Yandex, and others already use these vocabularies to power rich, extensible experiences.

Software Package Data Exchange (SPDX) is an open standard for communicating software bills of material information, including components, licenses, copyrights, and security references. swh-indexer doesn’t check that the license type specified in whichever metadata file is applicable. Instead, it is assumed that the license type is one of the formats specified in SPDX. The URI for the license object then points to the page for that particular license (for eg. Apple MIT License)

How does metadata help swh-search?

Software Heritage built and maintains an archive of open-source software source code. This sounds like and indeed is, a black box dump of gazillion lines of code. What use would this be? A bare archive can be analogous to the web pages of web 1.0 which were just displays of information. The archive would be useful only if humans or machines can interact with the archive. SWH-Search is probably the first feature that helps users interact with the archive.

The easiest way to look for a keyword in the repositories analyzed by the archive is to use the search feature of the origin endpoint. The complete syntax is: /api/1/origin/search/<keyword>/

For such a query, an array of hashes would be returned like this.

[

{

"origin_visits_url": "https://archive.softwareheritage.org/api/1/origin/https://github.com/borisbaldassari/alambic/visits/",

"url": "https://github.com/borisbaldassari/alambic"

}

...

]

Then there’s also the GUI search which makes the entire archive accessible through a Search Query Language. Click here to get an idea about that. My goal for this section is something else. How am I helping the search feature? How does the metadata obtained by the metadata indexer help the swh-search?

The answer is quite anticlimactic, I’m afraid. If you have gone through the S(search)QL documentation linked above, you’d know that every search query is composed of filters separated by and or or. There are several filters among which the most productive, for someone trying to search the archive the same way he/she would do Sourcegraph, is the pattern filter. The pattern filter can take either origin or metadata as a name. That’s right. metadata

Metadata would be keywords from all the intrinsic metadata fields supported on Codemeta / schema.

Closing words…

Wow! That was a long one. If you aren’t asleep by now, well, you’re in luck. I have a little bit more in store for you. As I write this blog, I’ve just updated my diff (D8079), hopefully for the last time before it is green to land. For the coming week, I hope to work on an indexer for NuGet (NuGet.config). I won’t lie to you, the work is indeed getting more interesting on all fronts. I’m planning to put another blog out soon on what I read about and liked from the book Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari. If you’re reading this, feel free to buy me this book.

Cheers!

This page was last updated at 2023-11-24 12:04.