Prologue

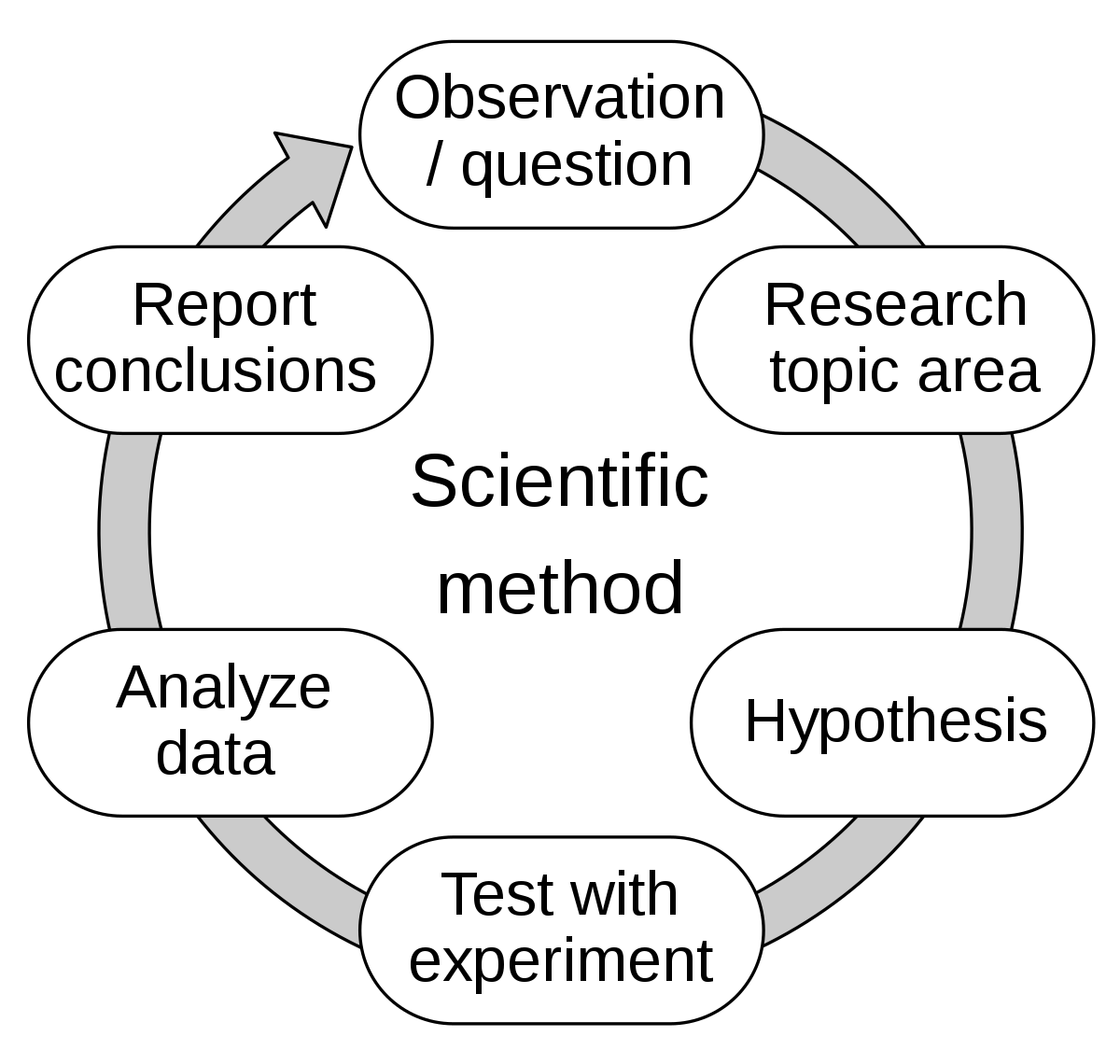

This chapter studies, at its core and at the risk of brevity, how the habits of societies can make or break movements. The study, not unlike every other chapter in the book, follows the same systematic pattern. The author provides a historical incident or a past study. The author goes on to analyse the incident by first posing some questions. A hypothesis is made for the questions. This is followed by designation of a test for the hypotheses. This test does one of two things, prove or disprove the author’s hypothesis(es). Or simply, the author connects the incident to a past study. This blog is my attempt to systematically reproduce the author’s methodology of study and see if the author’s approach seems intuitive to me.

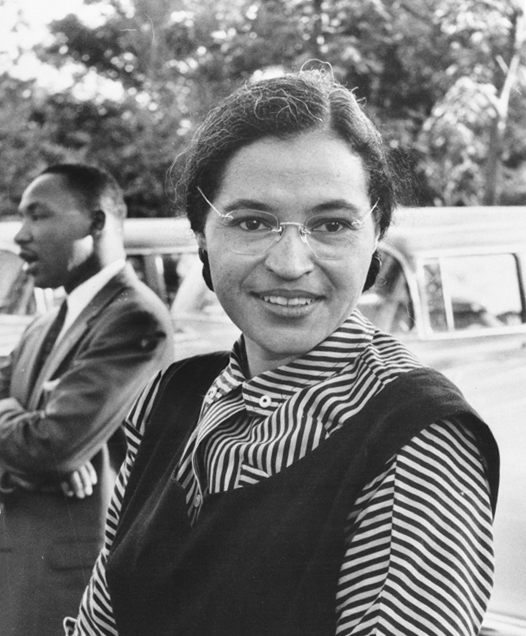

Rosa Parks

“The first lady of Civil Rights” and “The mother of the freedom movement” are two honours the United States congress has given the lady. Who is she? How was her saying “no” to segregation different from the others who did the same?

Rosa Parks was employed as a seamstress at a local departmental store. She was the secretary of the Montgomery, Alabama chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She had recently a center for training activists’ for workers rights and racial equality. Essentially, she had a positive relation with the society and had deep ties with the community.

E.D Nixon, Rosa's Lawyer

So when she was arrested on 1st December, 1955 for defying a bus driver’s order to vacate her seat for a white passenger, it just was different from the arrests of other negroes for the same causes. This lady was known by everyone. This lady simply did not deserve to Be. Locked. Up. Her activist lawyer, Mr. Nixon, saw the issue at hand for what it was. He knew that this arrest, if any, was what could stimulate a movement, an uprising, that could bring any impact to the cause of the civil right activists. With the Parks’ permission, he wished to fight this case in court. Though they lost the case, taking it to court had a profound impact on the civil rights movement in Montgomery, Alabama. Every black man and black woman now knew of the task at hand and what it was going to take to counter this unimaginable oppression.

Why?

While the first aspect that makes a movement successful is the ties of a person and the impact a person has on the community, it isn’t enough to wage a struggle that can promise results. Why should people go out in support of something? You may say, “bloody hell, they’re getting oppressed, that’s why!” But why should they risk what they have…? A job at a white man’s store, a job at a white lady’s home, a job at a white girl’s school… Why would someone risk these? It boils down to the same scenario as to why should or would someone leave the comfort of his or her bed to go for a jog? As many would prefer it, what’s the motivation?

Charlie, the learned author of this book, presents this in his own way. Imagine someone asks you to recommend him/her for a job. If the someone is a close friend, that’s an easy decision. Yes, of course, you can recommend him or her. Things get funny when you don’t exactly know the person. Why should you put your reputation at stake for that acquaintance of a someone…? This was what a Harvard PhD student at the time studied by conducting a survey of a little less than 300 people about how they got their jobs. What he found was not the answer you’d probably been expecting. I can assure you that it wasn’t what I was expecting.

Granovetter, now a Sociologist at Stanford

The PhD scholar, Mark Granovetter, called the latter kind of relationship “weak ties”. And he found from his survey that these weak ties were equally as, may be argued more, powerful than the strong ties a person has. Here’s an abstract from the book that best describes it:

In other words, if you don't give the caller looking for a job a helping hand, he might complain to his tennis partner,

who might mention those grumblings to someone in the locker room who you were hoping to attract as a client, who is now

less likely to return your call because you have a reputation for not being a team player.

Peer Pressure

The excerpt you have just read is textbook peer pressure if ever there was a textbook on peer pressure. And peer pressure is the second factor, second social habit that drives movements. Habits of peer pressure spread through weak ties. What does this mean? How does this work? Now comes the story of the Freedom Summer and the study, sociologist Doug McAdam from Arizona, conducted on it.

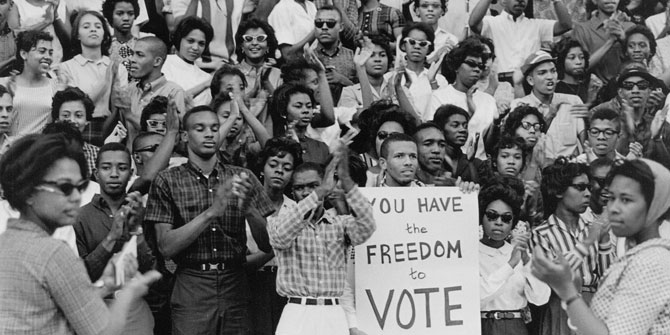

The Freedom Summer project was a programme to which youth from Harvard, Yale and other Northern universities applied to, for the summer of 1964. Volunteers would work to register as many African-American voters as possible for the upcoming elections. May not seem like it now, but it was dangerous back then. In the weeks prior to the project, some early volunteers were attacked and a few were killed by white supremacist groups and organizations. So by the time the project started, of the thousand selected applicants, more than three hundred backed off. Why was this happening? What was the cause for the change in mind? Why were so many backing out while hundreds more chose to stay on?

A Freedom Summer peaceful demonstration

The answer to this question, my dear readers, lies in the intricacies of peer pressure. McAdam, too, reached this conclusion, but only after a few disproven hypotheses.

Hypotheses

His first hypothesis was that students who ended up going to Mississippi probably had different motivations than those who didn’t. To test this he divided the applicants into two buckets. One was for people with motives like “self interested”, “test myself”, “to go where the action is” or “to learn about the southern way of life”, motives that seem… less motivational. In the second bucket went applicants with motives like “improve the lot of blacks”, “aid in the full realization of democracy” or “to demonstrate the power of nonviolence as a vehicle for social change”. Basically classified them as “self centered” and “other oriented” applicants.

However, the selfish and the selfless, according to the data, went South in equal numbers. Differences in motives did not

explain "any significant distinctions between participants and withdrawals," McAdam wrote.

His second hypothesis was that maybe those who stayed back had greater opportunity costs than those who went. For example, those who stayed back may have had girlfriends or husbands or jobs holding thm back. But the numbers told a different story for this hypothesis too. On the contrary, it was more likely that you would go if you were married or had a full-time job.

For his final hypothesis, each applicant was asked to list their membership in student and political organizations along with a list of ten people they would like to keep informed of their summer activites. This answered the question. The students who participated in the Freedom Summer were engrossed in social groups whose other members expected you to get on the bus. Period. So they got on the bus. Period. Those who didn’t get on the bus were in communities whose social habits didn’t expect you to get on the bus for such a project. These were groups like academic fraternities and the student government. And so they didn’t.

Doug McAdam

This was the proof, wasn’t it? What more can prove the effect peer pressure, that has grown from the weakest of ties, can have on a movement, on a cause? So, this was the second factor that made the Montgomery bus boycott as effective as it was.

The boycott

So on the Monday that Rosa Parks was eventually found guilty, a boycott of the city buses was called. There was a newspaper report on Sunday describing the plan of “Montgomery Negroes” to boycott the bus lines come Monday. This, funnily enough, was what fuelled the boycott. A “negro” mother of three who glanced at the article on the newspaper lying on the charpoy beside the dining table while serving the meals, decided not to use the bus the next day. And so did the “negro” gardener of the townhouse and the “negro” car mechanic, and hundreds, if not thousands of other Montgomery residents. But why?

This was peer pressure in action! By the time the article was written, only Parks’ friends had publicly committed to the protest. But once the paper was out, they all assumed, just like the white readers, that everyone else was already aboard the ship of revolution. And so, people with weak ties to Rosa Parks, felt the peer pressure to rally alongside their “Negro’ brothers and sisters and let the state know of their revolt against the State’s segregation laws. And let them know, they did.

The bus boycott

For, the next day, bus lines usually packed with hundreds of riders had only a few, if any, riders on the bus. King and his aides had convinced many “negro” taximen to charge their brother and sister “negro” riders only 10 cents a ride, the same as a bus ride. Come Monday evening, negro men and women, negro youth, were standing in groups at bus stops. They were cheering every empty bus that came and went while the drivers could only look at the crowd in disgust.

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

Thoughts

Prior to Parks’ arrest, several others had been arrested for breaking Montgomery’s stringent bus segregation laws, including Geneva Johnson (1946), Viola White (1949), Katie Wingfield (1949), Claudette Colvin (1955) and Mary Louise Smith (1955). What, then, was different? Rosa had strong ties in the community to get the movement started. She had the weak ties that were required to bolster peer pressure among the people to get the movement going. Finally, there was a leader, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who built on social habits in the right combination with peaceful resistance to oppression, learned from other movements around the world like Gandhi’s Non-Violence Movement and Nelson Mandela’s demonstrations against Apartheid.

What are my thoughts from the reading? I believe the facts and understandings are presented in a way worth admiring and learning from. Connecting the various incidents to the several studies the author must have surveyed is a skill worth having. Coming to the content of the chapter, it has helped me get a completely different perspective on peer pressure. Peer pressure, as I’m sure most of you would have believed too, seems like a negative thing. Something that can make people do things they wouldn’t normally do. I have been proven wrong in a very interesting manner. I reserve further comments on the topic for future blogs, as I ponder the ins and outs of what I have read.

Adios!

This page was last updated at 2023-11-24 12:04.